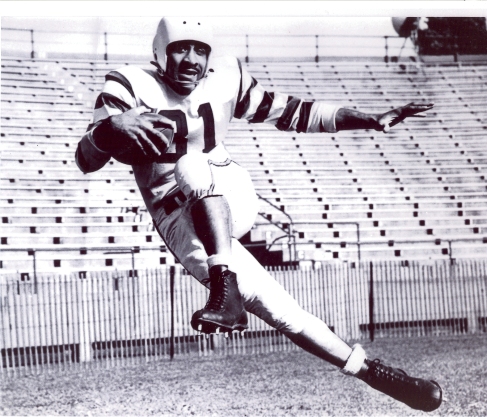

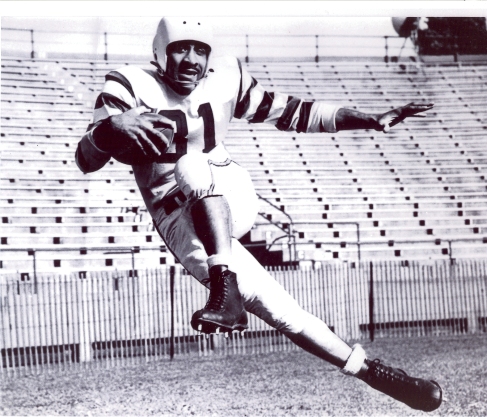

Ulysses Curtis

Born: May 10, 1926 (Albion, Michigan)

Died: October 6, 2013 (Toronto)

Ulysses Curtis burst onto Canadian football fields in 1950 with a running style so electric he was known as Crazy Legs.

Mr. Curtis’s churning, knees-high style made him elusive prey. His dramatic rushes helped lead the Toronto Argonauts to a Grey Cup title in his rookie season in a game remembered as the Mud Bowl. Toronto again claimed the Canadian professional football championship in 1952 with the fleet and powerful Mr. Curtis a valuable weapon in the arsenal.

Mr. Curtis, who has died in Toronto, aged 87, retired after five seasons as the club’s all-time rushing leader, and remains in fourth place on that list nearly 60 years later. His name can still be found elsewhere in the team’s record book for several rushing standards, as well as for his seven playoff touchdowns.

“He was a power runner, he had speed, he could catch,” said Nobby Wirkowski, 87, the quarterback who guided the Argonauts to the 1952 title. “He was an outstanding halfback.”

Mr. Curtis’s career was also notable in that he joined teammates Billy Bass and Marvin (Stretch) Whaley as the first blacks on the Argonauts roster as professional sports teams began to integrate following the Second World War. In his first month on the team, an opponent delivered a racial slur against Mr. Curtis during a game, resulting in an on-field brawl.

Mr. Curtis’s career was also notable in that he joined teammates Billy Bass and Marvin (Stretch) Whaley as the first blacks on the Argonauts roster as professional sports teams began to integrate following the Second World War. In his first month on the team, an opponent delivered a racial slur against Mr. Curtis during a game, resulting in an on-field brawl.

The player’s success on the football field is all the more remarkable for the fact he did not even play the sport until going to college after serving in uniform during the war.

Born on May 10, 1926, to Frances (née Hall) and William Curtis of Albion, Mich., Ulysses was likely named for the Union general who later became president, according to his son. Four years earlier, the family moved north from Jeffersonville, Ga., after being recruited by the Albion Malleable Iron Company. Will, a veteran of the World War, died in 1930 of pneumonia and the local American Legion post for black veterans was named in his honour.

Uly Curtis starred as a guard in basketball and as an infielder in baseball for Washington Gardner high school. He was lithe and dextrous. An older, huskier brother, Tom, told their mother to forbid him from playing football. After graduation in 1944, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, based for a time at Pearl Harbor. One of his assignments involved delivering munitions to Saipan in the Northern Mariana Islands. It was while in uniform in the Pacific that he met Larry Doby, an African-American baseball player who in a few years would join Jackie Robinson in breaking baseball’s colour barrier.

After being discharged, Mr. Curtis used his G.I. Bill benefits to cover tuition at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, an historically black college at Tallahassee. Since leaving school, he had grown two inches and added several pounds to his frame. A sprint star on the track, Mr. Curtis showed himself to be a raw but uncatchable force on the gridiron. He scored 27 touchdowns in his final two seasons with the Rattlers.

The professional Los Angeles Dons expressed interest in the fleet scatback, who stood 5-foot-11 and weighed 175 pounds. Meanwhile, Argos president Bob Moran received a clipping from the Pittsburgh Courier, which catered to an African-American readership, describing the exploits of an athlete named a Negro All-American in his junior and senior years. The Toronto team offered him a tryout. The prospect of avoiding American segregation was appealing, as was the paycheque on offer.

“I had received a letter from Argonauts which stated I would be paid $150 a game if I made the team,” he told Milt Dunnell of the Toronto Star in 1989. “Also, I would get $50 per week during the preseason. Doesn’t sound like much now but remember bread at that time was only 15 cents a loaf.”

In August, 1950, about 3,000 spectators watched the American import and fellow rookies join veterans in a split-squad practice. Crazy Legs made an immediate impression. “The husky halfback with the legs only slightly smaller than a dray horse’s ripped up a scrimmage in such startling fashion that even coach Frank Clair was seen to smile for the first time in two weeks,” reported Hal Walker of the Globe. The first time he touched the ball Mr. Curtis galloped 80 yards. The Argos agreed to pay him $200 per game.

Early in the season, Mr. Curtis was at the centre of an incident in which blows were exchanged during a game against the Ottawa Rough Riders. He objected to a hard tackle by Eddie Matthews, a guard “who needs no encouragement to rough up any opponent, especially a coloured one,” the Star noted. Newspaper accounts describe Mr. Curtis retaliating with a punch, for which he was cuffed in the face by another Ottawa player. In the ensuing melee, a pile of players wound up in a pack on the ground near the Argos bench. Later, it was revealed another Rough Rider, Howie Turner, who was from North Carolina, had taunted Mr. Curtis with a racial epithet.

The slur incensed the Argonauts coach, who was even more outraged when his protestations to Ottawa’s general manager were met by further disparaging racial remarks.

The two teams were to meet a few days later in Ottawa, but before the opening kick-off, according to an account in the Globe, Mr. Turner jogged over to the Toronto sidelines to apologize to the coach, who called over his star halfback.

“What I said last week was in a ball game, Ulysses,” Mr. Turner said. “I didn’t mean it and I want you to know I’m sorry.”

“Thank you,” Mr. Curtis replied. “Thanks very much.” The two men then shook hands.

The Argonauts finished in second place in the Big Four before knocking off the first-place Hamilton Tiger-Cats in a two-game, total points series. Three days later, the Argos faced Balmy Beach, champions of the Ontario Rugby Football Union, with the winner to advance to the Grey Cup against the Western champion. The Argos had little trouble with their crosstown rivals, winning 43-13, with Mr. Curtis scoring three touchdowns.

The 1950 Grey Cup game is remembered less for the score and any feats of athleticism than for the conditions, as a heavy snow followed by a quick thaw left the turf at Varsity Stadium looking like a slush pile at the start of the game and like the Western Front at the end. (At one point, Winnipeg’s injured Buddy Tinsley, stretched prostrate in a puddle, was thought to be drowning.) Led by kicker Nick Volpe, who booted two field goals and, in those days of two-way players, also made a touchdown-saving tackle, the Argos prevailed, 13-0.

The 1950 Grey Cup game is remembered less for the score and any feats of athleticism than for the conditions, as a heavy snow followed by a quick thaw left the turf at Varsity Stadium looking like a slush pile at the start of the game and like the Western Front at the end. (At one point, Winnipeg’s injured Buddy Tinsley, stretched prostrate in a puddle, was thought to be drowning.) Led by kicker Nick Volpe, who booted two field goals and, in those days of two-way players, also made a touchdown-saving tackle, the Argos prevailed, 13-0.

At season’s end, Mr. Curtis was named a first team all-star halfback, an impressive debut.

It was in the final game of the 1951 season during which Mr. Curtis became the unwitting protagonist of one of the odder plays in Canadian football history. The visiting Rough Riders were nursing an 18-12 lead when Mr. Curtis intercepted an Ottawa pass intended for Mr. Turner, his tormentor from the previous season. The Argo was racing along the sideline with a clear path to the end zone. “He’s on a sprint,” recalled Mr. Wirkowski, the quarterback. “Nobody’s going to catch him. Then, all of a sudden…” A figure darted from the Riders bench. Riled by the sight of an opponent about to score, Pete Karpuk shucked off his warming blanket and raced onto the field. He failed to tackle a startled Mr. Curtis, but slowed him enough for another opponent to catch up and bring him down on Ottawa’s 22-yard line.

It took the officials 15 minutes to sort out the situation, a delay during which spectators at Varsity Stadium began tossing snowballs. In the end, a 10-yard penalty was assessed. Happily for the Argos, they soon scored the touchdown denied Mr. Curtis by an illegal play. In his defence, Mr. Karpuk said he’d once been instructed the rule book did not prevent such an act. He was right and the Canadian Rugby Union added a more punitive clause to the rules just days later.

(The incident preceded by six years a similar though better remembered event in the 1957 Grey Cup game during which Hamilton’s Ray (Bibbles) Bawel intercepted a pass with a clear path to a major until a figure in civilian clothes tripped the speeding player. In the subsequent chaos, the culprit slipped away. Hamilton eventually won the game, but the identity of the tripper remained unknown until prominent lawyer David Humphrey fessed up decades later. Mr. Humphrey died in 2009. Mr. Bawel will mark his 83rd birthday on Nov. 21.)

Mr. Curtis concluded his third season with the Argos as the leading scorer with 80 points on 16 touchdowns, a Big Four record. He ran for 998 yards in 12 games. In a game against the Montreal Alouettes on Sept. 6, 1952, Crazy Legs romped for 208 yards, setting a club record that would last 36 years.

Under the direction of Mr. Wirkowski, the Argos won their second Grey Cup in three seasons in 1952 by defeating the Edmonton Eskimos, 21-11. Early in the second quarter, Mr. Curtis was stopped from scoring at the one-yard line. His quarterback punched the ball across in the next play from scrimmage. The championship would be the last enjoyed by the Argos for 31 years.

A knee injury ended Mr. Curtis’s career after just five campaigns. He had carried the ball 529 times for a total of 3,712 yards, averaging a spectacular 7-yards per carry. He had also rushed for 26 touchdowns (and would have had one more had it not been for Mr. Karpuk’s skulduggery).

Every offseason, he returned to Albion, where he worked at the metal factory and a glass factory. After leaving football, Mr. Curtis decided to become a Canadian citizen and settle in Canada with his young family. He became a teacher, including a stint at Associated Hebrew Schools, later spending more than 30 years in public school classrooms. He taught history, geography and physical education, and was a guidance counsellor at Downsview Secondary in North York, where he also coached the Mustangs senior football team.

Mr. Curtis died of natural causes on Oct. 6 at his home in Toronto. He leaves Catherine (née Williams), whom he had married in 1949 while both were juniors at Florida A&M. He also leaves a son and two daughters. He also leaves a daughter from a first marriage, which ended in divorce. Other survivors include five grandchildren, a sister, and a brother. He was predeceased by two sisters and three brothers.

Mr. Curtis was named an All-Time Argo by the club in a pregame ceremony in 2005. As long as 1983 this newspaper noted that Curtis was “an obvious but so far” neglected choice for the Canadian Football Hall of Fame. The failure to induct him, either as a player for five remarkable seasons or as a builder for his role in helping to integrate Canadian football, remains a puzzle.

Argos at practice (from left) Marv Whaley, Al Dekdebrun, Ulysses Curtis, Doug Smylie, Billy Bass

Argos at practice (from left) Marv Whaley, Al Dekdebrun, Ulysses Curtis, Doug Smylie, Billy Bass

1952 Toronto Argonauts

In 1962, he played with the Redskins in preseason exhibition games only to be a late cut. He then signed with the Ottawa Rough Riders.

In 1962, he played with the Redskins in preseason exhibition games only to be a late cut. He then signed with the Ottawa Rough Riders.