OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Arthur John Howie

Born: September 16, 1945 (Saltcoats, Scotland)

Died: June 21, 2016 (Duncan, British Columbia)

Member: Greater Victoria (B.C.) Sports Hall of Fame

Al Howie ran the length of Great Britain and the breadth of Canada. He ran into the record books and then ran off into obscurity.

Mr. Howie, who has died at 70, scampered across deserts, jogged through prairies, scuttled over mountain passes. The Scottish-born athlete — one of the greatest runners in Canadian history — belonged to the small fraternity of ultra-marathoners, runners who competed across vast distances for hours and days at a time.

Mr. Howie’s feats were outlandish, the distances covered so outrageous as to be comical. He won six-day foot races in California and seven-day races in New York. He once completed a marathon in Edmonton only to run the 1,500 kilometres to Vancouver Island to compete in a marathon in Victoria. He also ran from Winnipeg to Ottawa, competing in marathons in both cities. Most famously, he ran across Canada for two gruelling months in 1991. Still, his feats rarely earned more than a brief paragraph in the daily newspapers.

Had his specialty been the 100-metre dash, or the marathon — a mere jog in the park for Mr. Howie at 26-miles, 385-yards (42.195 kilometres) — he would have been a household name in his adopted land. Instead, he spent much of his running career in near-penury, a workingman who earned his daily bread in the woods of British Columbia and whose weekends were spent in a pitiless pursuit.

Mr. Howie stood out as an eccentric even in the offbeat world of road runners. He was called the Spartan Tartan, known for wearing a toque over long, flowing blond hair, his face covered by a bushy red beard. A T-shirt hung loose over a sinewy, 5-foot-8, 130-pound frame, while wee shorts decorated in a Union Jack motif revealed legs more spindly than powerful. He looked like a skinny Rob Roy, sounded like Scotty from Star Trek, and had the prickly temperament of Groundskeeper Willie from the Simpsons. He liked to drink beer before a race, a habit that infuriated some of his lesser competitors, and was known to have more than one afterwards. The beer helped ease the pain from blisters, he explained.

At times, his special skill seemed more curse than blessing.

“I have to admit,” he told the New York Times, “there are days when I wish I was good at something a little easier, like darts or pool.”

While other sports attracted corporate sponsors and large salaries, or offered fame worthy of an Olympic champion, ultra-marathoning remained the purview of the indefatigably obsessed. Sponsorships and prize money were scarce. Competitions featuring runners going in circles around a track for a week do not make for good television.

“I run on resentment, angrily pounding the blacktop,” he once wrote. “Why must I run on empty? Who do I get no support from my hometown? Mostly, I plod on because I have committed myself to this asphalt insanity and I simple don’t know how to quit.”

For his part, Mr. Howie felt less like he was helping to popularize a fringe sport then that he had been born a century too late.

“From 1870 to 1890, six-day races were the thing,” he told the journalist Jody Paterson. “The top prize was $40,000, which would have been an incredible amount back then. If I’d have been alive then, I’d have been rich, a Gretzky.”

Arthur John Howie was born in the Scottish coastal village of Saltcoats at war’s end on Sept. 16, 1945, to Mary Armour (née Lochead) and Arthur John Ewing Howie, a mariner who later served as chief steward for a shipping line. Before marriage, his father had been an amateur boxer, his mother a club champion swimmer. Family vacations included walking tours of the Scottish countryside, the boy racing ahead of his siblings to place a valley rock atop the cairns that grace Caledonian hilltops.

Young Arthur became known as Alfie when a new boy at school mangled his name. The nickname stuck until the Burt Bacharach and Hal Davis composition “Alfie” became a hit in 1966, forcing a shortening to Al to avoid answering the inevitable, tiresome question, “What’s it all about?” Scoring good marks at Ardrossan Academy, a secondary school, with little effort, Mr. Howie eschewed university for more hedonistic pursuits as a hippie enjoying the pleasures on offer in the late 1960s.

He worked for a time in a German factory, which provided enough income for an idyllic life in a Turkish fishing village until funds ran out.

A brief marriage to an American woman left him the single father of a son. When custody of the boy was challenged, Mr. Howie and a woman with whom he then had a common-law relationship moved to her Toronto hometown. Mr. Howie adopted an assumed name until a settlement was reached with his wife. He worked in a foundry in winter and as a stonemason in summer.

A daily three-pack habit of cigarettes proved difficult to quit. One day, frustrated by cravings, Mr. Howie, on impulse, began jogging in street clothes. He travelled about 16 kilometres before stopping. “I took up running to get rid of my aggression,” he once told the sportswriter Gare Joyce. A daily running regimen eased the symptoms of tobacco withdrawal.

One day, when his factory mates argued how long it would take a horse to travel from Toronto to Niagara Falls, Mr. Howie insisted he could do so in a day. They scoffed, yet he soon after successfully completed the 125-km run.

He became a father again, this time to a daughter, though the relationship with her mother foundered. Mr. Howie moved to the West Coast, where he again adopted an unstructured life of whim and poverty.

After getting a job operating a crusher at a copper mine on Vancouver Island, he commuted the 20 km between town and mine pit by sneaker.

In time, Mr. Howie’s escapades earned notice in British Columbia newspapers. When other people might drive, fly, or travel by bus between far-off cities, Mr. Howie ran because it was cheap. He often slept under the stars. In 1978, he ran 500 km from Victoria to Port Hardy at the north end of Vancouver Island to raise money for charity. In 1979, he ran from Victoria to Prince George to race in a marathon. (Another competitor was an unknown Terry Fox, running his first marathon on an artificial leg just eight months before launching his cross-Canada Marathon of Hope. Rick Hansen raced in his wheelchair at the event, six years before the start of his Man in Motion world tour.) In 1980, Mr. Howie finished third in the Edmonton marathon before running to Vancouver Island, where he finished 14th in the Royal Victoria Marathon.

In 1983, he ran from Winnipeg to Parliament Hill on Ottawa, enduring black fly bites outside Wawa, Ont., that caused his face to swell. A sponsoring brewery covered $100 in daily expenses and provided free samples of their product in exchange for the runner wearing a promotional T-shirt and cap. A company official estimated Mr. Howie consumed 18 bottles of their product daily. “Not that much,” Mr. Howie insisted. That same year, he won a 100-kilometre race in Toronto in 7 hours, 30 minutes, 31 seconds, nearly 90 minutes faster than the previous record. His strategy in an endurance race was to go out at a blistering pace for the first mile to dispirit his competitors.

In 1987, he completed 1,422 laps on the track at Centennial Stadium at the University of Victoria to break a Swedish runner’s mark for distance covered in a continuous run. Mr. Howie needed 104 hours, 29 minutes, 48 seconds. Told the record was his, he ran another 18 laps to cover the possibility of any miscalculation.

He ran from John O’Groats in Scotland to Land’s End in Cornwall in 11 days, 3 hours, 18 minutes in 1988, bettering the previous mark by more than 22 hours. The record has since been eclipsed.

In 1989, he became the first runner to complete the New York Sri Chinmoy Ultra-Marathon, an unforgiving 2,100-kilometre endurance race with an 18-day time limit. Mr. Howie finished in 17 days, eight hours, 25 minutes, 34 seconds. After more than a fortnight of sleeping less than four hours each night, he allowed himself the indulgence of a six-hour nap, waking in time to greet the second-place finisher.

On June 21, 1991, Mr. Howie was joined at Mile 0 in Newfoundland by the mayor of St. John’s, who ran alongside for the first kilometre of what would be a 7,295.5-km cross-continent odyssey. Within days, a scorching summer sun caused a severe burn to the skin on Mr. Howie’s upper lip, which turned black and began to peel. Afterwards, he wore long pants and a long-sleeved shirt, as well as a homemade cardboard chevron over his nose, leaving him looking like a child dressed up as a penguin. A great admirer of Mr. Fox and his thwarted quest, Mr. Howie knew as an able-bodied athlete he needed to do something special to gain attention. He set a pace of running more than 100-kilometres each day, the equivalent of about two-and-a-half Boston Marathons. Every day. For 72 consecutive days.

The grand trek ended to the skirl of bagpipes and the cheers from about 100 spectators as Mr. Howie plunged into the salt waters at the terminus of the Trans-Canada Highway in Victoria. His journey, called the Tomorrow Run ’91, raised $527,400 for the Elks Club’s Royal Purple Cross Fund for Children. Mr. Howie celebrated by downing two beers and glass of champagne. The feat gained him notice in the Guinness World Records book.

Incredibly, just two weeks later, he returned to New York to defend his title, breaking his own standard in the 2,100-km Sri Chinmoy race with a time of 16 days, 19 hours.

In 1993, Mr. Howie won the six-day Gibson Ranch Multi-Day Classic run in California. He completed 180, 120, 111, 115, 107 and 109 kms on successive days on a loop through a county park outside Sacramento. He ended his competitive career in 1999.

Mr. Howie battled health problems in his years as a runner. He said he was diagnosed with brain cancer which he treated with a macrobiotic diet. He also developed diabetes, which he controlled by paying strict attention to blood-sugar levels.

What little money he earned in all his years of running came from labour as a mason, a scallop farmer, and as a tree planter, an arduous, piecework job that rewards singleminded obsessiveness and for which he was uniquely qualified.

“He was socially inept in many ways,” said Claudia Cole, who married Mr. Howie in 1987 and from whom he was estranged. “A lovely man, but he couldn’t get the nuance of human action. Same with dogs. He had to be warned if a dog’s ears were back.”

In recent years, Mr. Howie lived in an assisted-care facility on Vancouver Island.

Mr. Howie died on June 21 in Duncan, B.C. The cause of death is unknown although he was in poor health with complications from diabetes. He leaves Ms. Cole. He also leaves a son, Gabriel Howie, of Ardrossan, Scotland, and a daughter, Dana Corfield, of Mississauga, Ont., and Cusco, Peru, as well as an older sister, Elizabeth Howie, and a younger brother, Ian Howie, both of whom still live in Saltcoats.

In recent years, a journalist and a retired professor in Victoria campaigned to gain recognition for Mr. Howie’s achievements, resulting so far in the runner being inducted into the Greater Victoria Sports Hall of Fame in 2014.

Mr. Howie is one of four athletes celebrated along the Dallas Road waterfront in Victoria, where a plaque at Mile Zero commemorates his cross-Canada trek. Nearby, a statue memorializes the great Terry Fox. Others honoured are disabled runner Steve Fonyo and swimmer Marilyn Bell, who conquered the Juan de Fuca Strait. Mr. Howie, the most obscure of the quartet, is among august company.

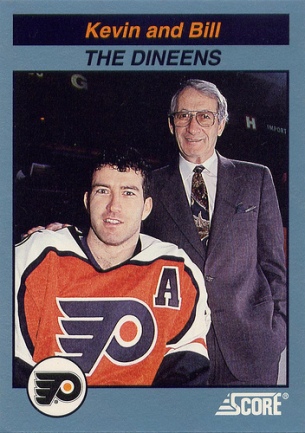

The right winger earned a colourful nickname early in his career as The Fox. “It comes from my days as a single guy,” he once said, “when I used to miss the odd curfew now and then.” Whatever his early reputation as a lady’s man, his marriage to the former Patricia Sheedy lasted 53 years until her death in 2010.

The right winger earned a colourful nickname early in his career as The Fox. “It comes from my days as a single guy,” he once said, “when I used to miss the odd curfew now and then.” Whatever his early reputation as a lady’s man, his marriage to the former Patricia Sheedy lasted 53 years until her death in 2010. In 1957, he was part of an eight-player trade with the Chicago Black Hawks, a deal widely seen as punishment administered by Red Wings management for having been supportive of the formation of a players’ union. In six NHL seasons, he scored 51 goals and 44 assists. He had a goal and an assist in 37 playoff games.

In 1957, he was part of an eight-player trade with the Chicago Black Hawks, a deal widely seen as punishment administered by Red Wings management for having been supportive of the formation of a players’ union. In six NHL seasons, he scored 51 goals and 44 assists. He had a goal and an assist in 37 playoff games.

Mr. Golab, who has died in Ottawa at 97, was named Canada’s male athlete of the year in 1941. He would later be inducted into five sports halls of fame, despite having spent two of his prime playing years battling the Nazis.

Mr. Golab, who has died in Ottawa at 97, was named Canada’s male athlete of the year in 1941. He would later be inducted into five sports halls of fame, despite having spent two of his prime playing years battling the Nazis. The following season, Mr. Golab suffered a severe back injury after a hard tackle by Eddie Zock of the Toronto Argoanuts. His season was at first thought to be over, but he recovered to help the Rough Riders defeat Toronto’s Balmy Beach team in the only two-game, total-points Grey Cup showdown ever played. The Rough Riders claimed the Dominion football championship with an 8-2 victory in Toronto followed a week later by a solid 12-5 win in Ottawa. Nursing two injured ribs and wearing a special brace, Mr. Golab made a key interception of a Balmy Beach pass in the second game, evading a half-dozen tacklers to return the ball 25 yards.

The following season, Mr. Golab suffered a severe back injury after a hard tackle by Eddie Zock of the Toronto Argoanuts. His season was at first thought to be over, but he recovered to help the Rough Riders defeat Toronto’s Balmy Beach team in the only two-game, total-points Grey Cup showdown ever played. The Rough Riders claimed the Dominion football championship with an 8-2 victory in Toronto followed a week later by a solid 12-5 win in Ottawa. Nursing two injured ribs and wearing a special brace, Mr. Golab made a key interception of a Balmy Beach pass in the second game, evading a half-dozen tacklers to return the ball 25 yards.

His sudden death deeply affected his colleagues at ESPN, including television personality Stephen A. Smith, who considered Mr. Saunders a mentor and who broke down on air. Fellow broadcaster Hannah Storm struggled to maintain her composure when announcing the news of his death live on SportsCenter from Rio de Janeiro, where she was covering the Olympics.

His sudden death deeply affected his colleagues at ESPN, including television personality Stephen A. Smith, who considered Mr. Saunders a mentor and who broke down on air. Fellow broadcaster Hannah Storm struggled to maintain her composure when announcing the news of his death live on SportsCenter from Rio de Janeiro, where she was covering the Olympics.

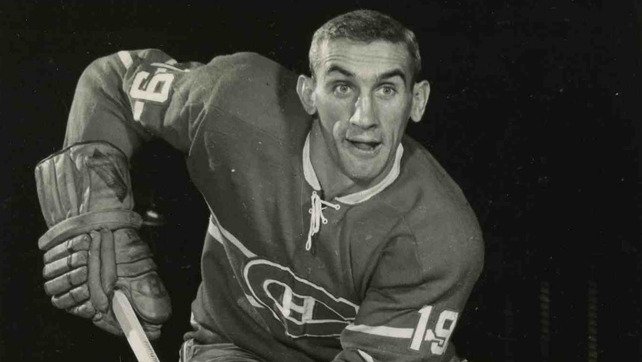

In the end, though, he was remembered long after he retired for two incidents. In a 1959 fight, Gordie Howe performed a rhinoplasty on Mr. Fontinato’s prominent proboscis with his knuckles. Four years later, the defenceman’s career ended when he was left paralyzed after a sickening collision with the boards. That he recovered from both was a testament to his ruggedness.

In the end, though, he was remembered long after he retired for two incidents. In a 1959 fight, Gordie Howe performed a rhinoplasty on Mr. Fontinato’s prominent proboscis with his knuckles. Four years later, the defenceman’s career ended when he was left paralyzed after a sickening collision with the boards. That he recovered from both was a testament to his ruggedness. LIFE magazine offers some post-fight advice for Lou Fontinato.

LIFE magazine offers some post-fight advice for Lou Fontinato.

Football’s offensive line is a front-line trench for large men whose job it is to protect the quarterback and open paths for runners. When guards and tackles fail, a quarterback is sacked, or a running back tackled.

Football’s offensive line is a front-line trench for large men whose job it is to protect the quarterback and open paths for runners. When guards and tackles fail, a quarterback is sacked, or a running back tackled.